In December 1998 Phil Lesh had a liver transplant.

His

surgery and recovery were a huge success. We owe thanks to the Mayo Clinic

(in Jacksonville, FL, one of the best transplant clinics in the country),

Dr. Steers (innovator in techniques of liver transplants and chief surgeon

for Phil's surgery), the HVC Global Foundation (grassroots Hepatitis awareness

organization), the loving family and their deceased who made the organ donation,

and to the fans and family who came together with love and healing energy.

His

surgery and recovery were a huge success. We owe thanks to the Mayo Clinic

(in Jacksonville, FL, one of the best transplant clinics in the country),

Dr. Steers (innovator in techniques of liver transplants and chief surgeon

for Phil's surgery), the HVC Global Foundation (grassroots Hepatitis awareness

organization), the loving family and their deceased who made the organ donation,

and to the fans and family who came together with love and healing energy.

And

we thank Phil Lesh for remaining comitted to raising our awareness of

organ donorship and other health issues related to Hepatitis.

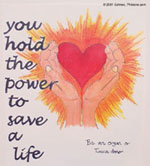

As Phil has reminded us, it is very important to notify your family,

preferably in writing, of your desire to be an organ donor (in addition

to putting the pink stamp on your driver's license or whatever it is in

your state).

If you're having trouble coming up with something, borrow from Phil's

phrasing :

' In the event of my demise it is my irrevocable desire to be an organ

donor '.

If your family decides against it, ultimately, they will know how you

felt or what your

wishes would be.

For more information, please visit our links below:

Phil Denver Blood Drive - Huge Success!Phil Lesh, former organ transplant recipient, has been on a crusade to promote the urgent need for blood and organ donations. Phil has been raising awarness by visiting local blood centers throughout the nation and encouraging fans to donate blood.

The

previous record of 77 pints of blood donated during a Phil blood

drive was broken this Saturday in Denver. About 251 people were

present to donate with 191 units actually donated! All

blood donors received a signed poster by Phil Lesh. For

more information on blood donation please visit |

|

Phil Lesh - Donor Awareness Rap

Santa Barbara County Bowl, 8/22/99

Santa Barbara, CA

I'd like to thank you all for coming out tonight, we've been having a great time on this tour. It's unfortunate this is the last one - we've been having a really good time.

I'd like to speak to you all about something kind of serious. I'm only here because I had an organ transplant earlier (the end of last year) and the people who were noble and generous enough to OK the organ donorship of one of their loved ones had to go through a really traumatic experience.

I encourage everyone who is interested in becoming an organ donor and really has a desire to give in the case of their demise not only to become an organ donor, and not only put the stamp on their driver's license, but to notify your family.

you and are close to you (who will be completely traumatized, it will be a tragic occasion). If you have written out something for them saying "I really want to be an organ donor just in case of my untimely death". Then that would make that decision so much easier for them.

So all I can say is I bless the folks that did it for me. Please be an organ donor and give blood. Thank you.

U.S.

plans national organ donor card

Legal document would help ensure deceased’s wishes

WASHINGTON,

April 5

- In a major effort to increase organ donation, federal officials are

devising a national organ donor card that they hope will make clear potential

donors’ wishes.THE IDEA is to give transplant coordinators a stronger

case for proceeding with donation, regardless of a family’s

permission, by making the donor cards legal documents that carry more

weight than a driver’s license or unofficial donor card.  It

is one element of a plan that Tommy Thompson, secretary of the Health

and Human Services Department, plans to make public later this month,

according to an agency official speaking on condition of anonymity.It

also is likely to involve a media campaign, an effort to work closely

with businesses and states to promote donation, and new ways to encourage

increasingly popular living organdonations. In addition, the budget President

Bush is sending next week to Congress will include an additional $5 million

for organ donation and transplant activities, an increase of 33 percent.

Since taking office, Thompson has talked regularly about organ donation,

prodding his audiences to sign donor cards. “It’s odd to me

that in America, this most compassionate country in the world, we have

so many people that are dying because of lack of organs,” he told

reporters last week.

It

is one element of a plan that Tommy Thompson, secretary of the Health

and Human Services Department, plans to make public later this month,

according to an agency official speaking on condition of anonymity.It

also is likely to involve a media campaign, an effort to work closely

with businesses and states to promote donation, and new ways to encourage

increasingly popular living organdonations. In addition, the budget President

Bush is sending next week to Congress will include an additional $5 million

for organ donation and transplant activities, an increase of 33 percent.

Since taking office, Thompson has talked regularly about organ donation,

prodding his audiences to sign donor cards. “It’s odd to me

that in America, this most compassionate country in the world, we have

so many people that are dying because of lack of organs,” he told

reporters last week.

ORGAN

SHORTAGE

More than 75,600 patients are waiting for organs, and more than 6,000

of them die each year. The number of waiting patients has grown five times

as fast as the supply. Much of the effort to increase donation has focused

on getting Americans to think about donation ahead of time and to talk

to their families about what they would want. The national donor card

would represent a more

structural change, aimed at helping the transplant coordinators who talk

with families about donation. The card would give those coordinators,

when dealing with families, “a really strong basis for saying, ‘We

intend to proceed unless you have a strong predisposition otherwise,”’

said the department official who described the plan. Now, most transplant

coordinators will tell family members if their loved one signed a donor

card but will leave it to the relatives to decide whether to abide by

the deceased’s wishes. The new cards would allow coordinators to

go a bit further, the official explained, by presuming that someone who

has a signed card will become a donor unless coordinators are told otherwise.

The cards would include a place for witnesses to sign

and for donors to specify which organs they wish to donate and whether

they want to include tissue and eyes.

MORE LEGAL

WEIGHT

The idea is to give the documents more legal weight and to prompt families

to discuss the issue in a manner worthy of a legal document, officials

said. Anything that prompts discussion is likely to be helpful, said Susan

Gunderson, president of the Association of Organ Procurement Organizations

and director of a Minnesota organ bank. Most families that know their

loved one’s wishes are likely to honor them, she added, but the new

donor card could break the tie in families that disagree about whether

to donate. Federal officials say the cards would supplement, not replace,

the donor cards that now exist, and could become a model for states or

others that wish to adopt them. They would be handed out at events where

donation is promoted through other parts of the initiative.

The department also wants to find ways to help coordinators find out whether

a potential donor has signed a donor card. Some states have registries,

but not all are easily accessible, especially after business hours or

from another state. But Thompson is unlikely to recommend a national registry,

at least not initially, given that it would be expensive and of questionable

effectiveness, officials said

Transplant Network Aims to Ensure Organs Get to Sick

By Laura Meckler

Nov. 16, 2000 — The nation’s organ transplant network is set to approve new rules for distributing scarce livers aimed at making sure the sickest patients are truly at the top of the waiting list. But the proposal being considered does nothing to break down geographic barriers that keep most organs in the communities where they are donated, even if there’s someone sicker in the next city or state over.

Rather, it would create a more precise scale for determining how sick waiting patients are, allowing the network to direct more livers to the sickest patients.

The United Network for Organ Sharing, which is expected to endorse the new plan today, must submit its proposal to the Department of Health and Human Services for approval. HHS officials, who have been demanding more sweeping changes, said they are prepared to accept the proposal, at least for now.

Supply and Demand Woes

The problem comes down to supply and demand. In 1999, there were 4,698 liver transplants performed, but 1,753 people died waiting. More than 16,000 liver patients are waiting today. Transplant centers, which depend on a reliable stream of donated organs to run their programs, also have an interest in maximizing the number of organs that come their way.

A network committee considered 17 plans for sharing livers over broader areas and a majority concluded that none of them would save a substantial number of lives, said Dr. Richard Freeman, a liver surgeon at Tufts University who chaired the committee.

“I really think this whole business of broader sharing is the wrong thing to be focusing on. It helps some but it disadvantages others,” he said. “It’s so divisive, it’s so unproductive, it’s so ridiculous. It’s a waste of time.”

One proposal, he explained, would have saved only about 20 lives per year, which he called a “drop in the bucket.” But broader sharing is what the HHS has been pushing since early 1998, when Secretary Donna Shalala dramatically declared that patients are dying simply because of where they live. After Shalala issued her regulations directing the network to break down geographic barriers, HHS and the transplant network plunged into outright battle over the best way to distribute organs.

In the end, it appeared as if HHS had won. Its regulations took effect after several congressionally imposed delays. And faced with competition for the job of distributing organs, the network agreed to a new contract that spelled out every detail of the regulation.

Now the network is required to submit a new plan for distributing livers, and it has stuck with its initial position against breaking down sometimes arbitrary geographic lines, much to the dismay of some patient groups.

Is HHS

Skirting the Issue?

“Once again they’re skirting around the issue of distribution,”

said Craig Irwin of the National Transplant Action Committee.

The network does propose a major change in the way waiting patients are

ranked.

Patients are now grouped into four broad categories. Within each group,

the length of time that a patient has been waiting determines who gets

the liver. But many transplant experts believe waiting time is a poor

measure of the severity of illness.

The new policy would still give first chance to Status 1 patients —

those who become suddenly ill and are expected to die within a week. Everyone

else would get a number, with the highest numbers for the sickest patients.

Patient scores would be determined by a combination of medical factors

including the body’s ability to form a blood clot; the ability to

break down the hemoglobin; and kidney function, which can be affected

by a failing liver. The system, developed by the Mayo Clinic, is known

as MELD, for Mayo End-stage Liver Disease.

HHS officials say they will wait to see how the new severity scale functions

before demanding that the network reconsider the issue of geographic boundaries.

It was impossible to run computer models on broader sharing under this

new system because there is no data yet on which patients would be affected,

said Lynn Wegman, director of the Division of Transplantation.

There should be enough data in a matter of months to return to the issue,

she said.

Other organs are also distributed along geographic lines, but livers have

engendered the most controversy. That’s because patients whose livers

fail have no other options, and donated livers can survive outside the

body for 24 hours before transplantation, meaning they can be safely transported

to other parts of the country.

White House, Senators OK Plan for Organ Transplants Medicine:

New system seeks to end struggle over how the scarce resources are allocated. Full Senate approval seen soon, then meetings with House.

By MARLENE CIMONS, LA Times Staff Writer

WASHINGTON

April 13, 2000 -The Clinton administration has crafted an agreement

with key senators on legislation to revamp the nation's organ transplant

system, pointing the way toward an end to the contentious two-year struggle

over who decides how these precious resources are distributed, senators

and administration officials said Wednesday.

WASHINGTON

April 13, 2000 -The Clinton administration has crafted an agreement

with key senators on legislation to revamp the nation's organ transplant

system, pointing the way toward an end to the contentious two-year struggle

over who decides how these precious resources are distributed, senators

and administration officials said Wednesday.

The compromise measure, hammered out late Tuesday night among administration officials and Sens. Bill Frist (R-Tenn.) and Edward M. Kennedy (D-Mass.), was approved unanimously Wednesday by the Senate Health, Education, Labor and Pensions Committee. It will be sent to the full Senate for a vote after next week's congressional spring break, where it is expected to be approved.

The legislation differs, however, from the House bill passed last week--a version President Clinton has promised he would veto--and differences will have to be resolved in a House-Senate conference committee. The Senate bill "will help to balance the difficult ethical and medical decisions that accompany decisions about how organs are distributed," said Frist, who was a transplant surgeon before being elected to the Senate.

The compromise, he said, "is in the best interest of all patients because it focuses on developing new policies based on scientific data, medical principles and equity."

Health and Human Services Secretary Donna Shalala said that the compromise, if enacted, "would provide a sound foundation for moving toward a better, fairer" system. She acknowledged that "no single party achieved everything it wanted" with the Senate bill but that it represents "a day-and-night improvement" over the House measure.

But the House Commerce Committee, which wrote the House version, called the Senate bill "misguided" and a thinly disguised White House plan to give Shalala more authority. Committee Chairman Thomas J. Bliley (R-Va.) remains "committed to providing the best protection for organ transplant patients," it said.

The Senate legislation skirts the most divisive issue: the argument over how to distribute scarce organs. But it sets up a mechanism to resolve fights between the federal government and the United Network for Organ Sharing, the private contractor that runs the system, by establishing a panel of outside experts to mediate future disputes.

The current controversy arose over the administration's attempt to change the organ network's policy of distributing organs in local areas first before offering them regionally and then nationally. Shalala's department sought to ensure that the sickest patients received organs first, regardless of where they live.

The House bill, siding with the network, would remove transplant oversight from HHS and give it to the network. Under the Senate bill, however, the outside panel would have the authority to make final decisions on policy, based on guidelines set into the law. The panel--made up of 21 experts, such as surgeons, clinical researchers and medical ethicists--would be chosen by the HHS secretary, the transplant network and the Institute of Medicine. Moreover, those guidelines would require development of a policy that would seek to reduce disparities in access that result from geography--a requirement representing a compromise with the administration, which sought to eliminate the disparities.

The Senate bill essentially would permit the organ network to write allocation policy but would permit the committee of experts to intervene if the government disagrees with the private contractor. The panel would have the final word, based on the guidelines. "This is not an easy issue to wrestle with--there aren't any evil people involved in this who are trying to do bad things," said Mark Rosenker, the network's managing director and assistant executive director for external affairs. "Everybody wants to do the right thing. We all just have different ways of getting there."

The issue has commanded increasing attention at a time when the nation is experiencing a crucial shortage of organs. Every day, according to medical estimates, 12 Americans die while waiting for an organ, and about 68,000 people are waiting for transplants at any given time.

Simultaneously,

advances in transplantation have made the medical procedure increasingly

successful, putting even greater pressure on the organ allocation system.

Doctors look for liver transplant alternatives

(taken from

cnn)

October

3, 1999 - Dallas

- Robert Pennington believes he's alive today because of a pig that his

family calls Wilbur. The 19-year-old suffers from liver disease. His name

was put on a transplant waiting list, but no livers were available.

Then Dr. Marlon Levy, a transplant surgeon at Baylor University Medical Center, offered an alternative: a procedure using a dead pig's liver. But not a liver from an ordinary pig. "They're genetically modified to try to prevent a reaction between the human blood and the pig liver," Levy said.

Pig liver

used as a filter

Pennington didn't actually have the pig's liver transplanted into his

body. Instead, his blood was run through the pig's liver in a procedure

called xenoperfusion. A tube was placed in a vein in Pennington's leg,

and his blood was siphoned through a pump. The blood was heated, oxygen

was added, then the blood was filtered through the pig's liver and returned

to Pennington's body. "I think it's impossible to say whether they would

have lived long enough to receive their liver (transplant) had we not

had this bridging technology," Levy said. "But I'd like to think that

made the absolute difference in their survival."

No replacement

yet for human livers

The pig liver was used to temporarily keep Pennington alive until a human

liver became available, but surgeons at Baylor hope to one day transplant

pig livers into humans. There is concern, though, that humans could pick

up a virus from pigs. "We need to have animals genetically altered to

the point where we believe we do not see an immune response of that dangerous

kind," said Dr. Goran Klintmalm, director of transplantation at Baylor

University. "The promise of xenotransplants has been around for many years,

and still has not been fulfilled," said Dr. Achilles Demetriou of Cedars-Sinai

Medical Center. "My guess is it will not be fulfilled in the immediate

future."

Bioartificial

liver also gives patients hope

Demetriou has been working on a device he calls a bioartificial liver.

It would use cells from pig livers to remove toxins in a technique similar

to kidney dialysis. After sudden liver failure due to medication poisoning,

Molly Koch, was put on the device for two days until a human liver became

available. "I wouldn't be here right now if it wasn't for the machine,"

Koch said. Doctors at Cedars-Sinai have used the machine on 26 patients,

and 23 still are alive. Demetriou said there was an unexpected bonus.

"We did find in about six patients when we kept them alive for several

days, their liver recovered spontaneously so they actually got better

without the need for a transplant," Demetriou said. Last year in the United

States, there were more than 13,000 people on waiting lists to receive

liver transplants. Fewer than 5,000 received new livers; many others died

while waiting. Many doctors believe that even if more donors become available,

the real solution to ending the organ shortage is animal-to-human transplants.

And they believe success stories like Pennington's and Koch's indicate

that could become a reality in the next decade.